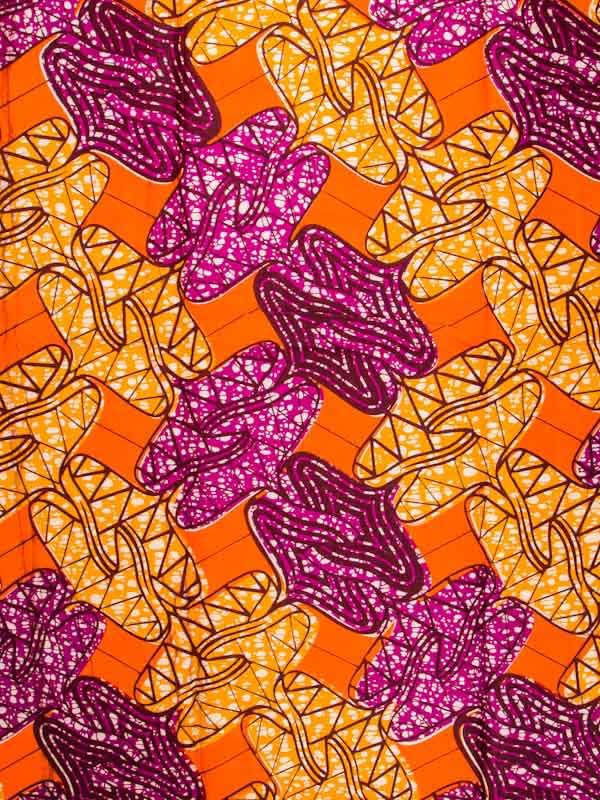

When you did your IG takeover for Kupfer in the lead up to exhibition The Gaze Is a Singular Act (September 2020), you were researching different the types of patterns used in fashion, architecture and decoration: the history of Dutch wax print, the use of fractal patterns in African architecture, and the designs of William Morris. How did your interest in patterns come about?

My interest in patterns originated from when I used to paint pictures from old family photographs. After doing this for some time I found that I was much more interested in the clothes that they were wearing rather than the people. Therefore, I began simplifying the human figure into shapes and outlines, and emphasising the patterns, colours and shapes of the clothing. I was particularly interested in the history of Dutch wax fabrics, fractal patterns in African architecture and William Morris designs because of my many trips to The British Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), old family photographs and clothing. For example, I found numerous Dutch wax garments in my attic and my parents’ wardrobe in my house. I also saw many traditional African textiles at The British Museum. After seeing these things, it led me to further research the history of these textiles and ancient African pattern-making. This also led me to African Fractals used in their architecture, and a book that really explained this well for me was Ron Eglash’s African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. The book explains how fractals are used in many aspects of traditional pattern-making in Africa, which is distinct from any other culture around the world. I was also inspired by William Morris’ designs due to his use of floral imagery. My mother used to wear a variety of flowery dresses which reminded me of his designs. It also represents how textile designs from these two regions (Britain and West-Africa) have influenced my life.

The figures in your paintings never have distinguishable facial features. Is this an intentional choice?

Yes, I choose to do this in order to make the viewer look at the patterns rather than the characters. I also depict the person as an outline, so that figures look like another shape alongside the numerous symbols and patterns in the painting. I want the audience to look at the painting several times and discover new shapes and patterns within the more prominent shapes and patterns. The observer can also put themselves or their own family in my faceless portraits to connect with the idea of knowing about distant family members who they have never met in real life. They can also bring their own stories into my artworks by inserting themselves in my portraits. In addition to this, the lack of facial features represents the fact that I do not know these people very well; they are simultaneously connected and disconnected to me. It serves as a way for me to relate to my heritage in a superficial way, by painting generic, indistinguishable people, wearing stereotypical patterns associated with Africa.

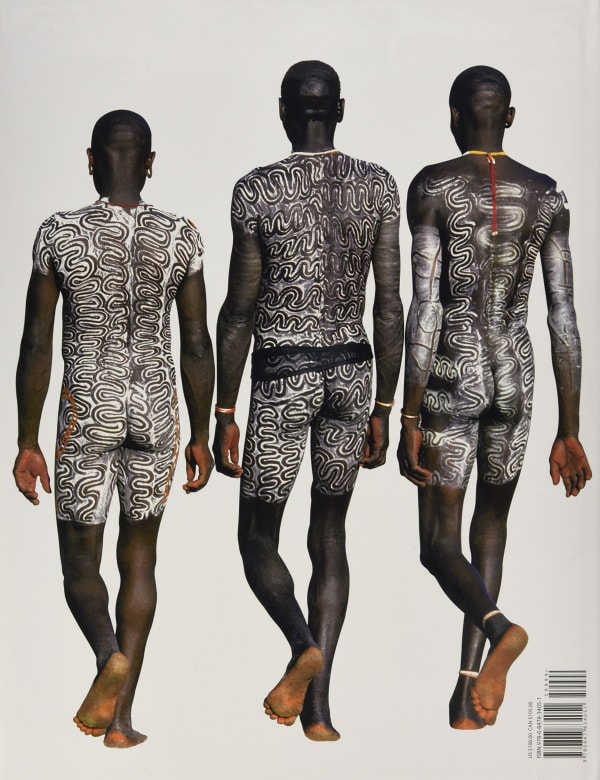

Now focusing on the series of photographs you showed at Kupfer, you mentioned that your first idea was to create an installation using the patterns that already appeared in your paintings. However, with the first lockdown you suddenly found yourself without access to your studio at Slade and decided to create this work in your own bedroom. Do you see these photographs as a documentation of a performative work?

I see them as a performance and photography series. When I was taking the photographs, I simultaneously filmed myself doing everyday things in my bedroom such as, eating, sleeping, and drawing. The video that I filmed while doing this photography is called Patterns In My Bedroom. I asked my sister to help me take the photographs, and it was my first time experimenting with photography, performance, and film. The performance was a result of spending a great deal of time in my bedroom by myself making art during the lockdown. I also drew several shapes and symbols inspired by my family’s clothing, my memories of the people that wore these patterns, and the history of these textiles. It also was a type of therapy, as I found it therapeutic to draw the same shapes repeatedly, and it helped my mind focus on one thing. When the viewer looks at my photographs, I hope that they will see the patterns as a type of symbolic writing which can be interpreted differently by each person. I see the black and white motifs as a kind of Rorschach Test, where an ink blot is shown to a therapy patient for them to interpret what they think it is. This helps the therapist determine the patient’s mental state and characteristics, which is particularly helpful when individuals are reluctant to express what is on their mind. I think this therapeutic side of my work helps the audience to interact with my photography, making it a performance in itself.

In relation to the bedroom series, you mentioned that you take inspiration from clothing belonging to relatives that you don’t know personally. Do these relatives live in another part of the country/ another country? Is the use of these clothing patterns a means of somehow attempting to reconnect with your family history?

The photographs were taken mostly by my uncle and some other family members in the 1960s to the 1990s. I came across them accidentally while cleaning my attic. Some of the pictures were taken in Nigeria and some in the UK. However, many of the people in those photographs have either passed away or live far away from me. The depiction of these people in my paintings and the use of patterns inspired by their clothing is a way for me to connect with them. For example, the use of flower patterns influenced by my mother’s dresses remind me of being with her and all the things we used to do together. For me, it is also a way to learn about Nigerian culture and history because I have never been there. I also want to mix British and West-African textiles and history to investigate how these two cultures have influenced my own life.

It is interesting to note how your appropriation of patterns goes way beyond their decorative aspect. The patterns are indeed very seductive and definitely grab the viewer’s attention, but in your paintings and photographs they always bring an underlying narrative related to personal and social histories of diaspora. How important is it to you that these narratives come across in the work?

Many of the patterns were influenced by Adinkra symbols, which are from Ghana and represent aphorisms or concepts. Some of the motifs come from family members’ clothing and traditional dresses, some come from William Morris designs and some come from ancient Oceanic and African pottery and textiles at the British and the V&A Museums. It is not important for the viewer to know where the symbols come from or what they mean when they first encounter my work. I want them to bring their own interpretations and stories to the motifs, so that the audience can become part of the art. In addition, the patterns are only influenced by these things, they are not an exact replica of the symbols that have inspired me. I have designed new symbols to invent my own language, and to represent my own unique identity, being born and raised in Britain, with West-African heritage. I also want to create an artificial representation of Africa, as I only know about it through the British and Western perspective.

When I first saw the images of the bedroom series I was instantly reminded of Roger Caillois’ 1935 essay Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia, in which he contends that camouflage in nature doesn’t serve any defensive purpose, but rather works against self-preservation as it provokes a ‘loss of self’. You mentioned in your description of this work that you wanted your body to be disguised in the environment like a chameleon in its natural habitat. It seems to me that your intention in this series is actually the opposite of what Caillois claims: namely, to convey a sense of belonging, or ‘recovery of self’. You also speak of the therapeutic effect of repetition when drawing patterns, which also seems to point towards a structuring of the self rather than a dissolution of it as proposed in Caillois’ reading of camouflage.

Indeed, in my photography series Patterns In My Bedroom I wanted to use patterns as an opportunity to camouflage myself in my bedroom, but also to show how nature has influenced my pattern-making. By creating a new environment and adorning myself with patterns, I was able to become a different character in my own made-up world. This transformation allowed me to express my different personalities, something I would have been too shy to do without wearing the face paint and costume. Although my work helps me to convey a sense of belonging, I also agree with Caillois’s writing about self-preservation. In my photography/ performances I want to be hidden within the patterns, and for people to stop and look closely to notice me. This is like a chameleon, that changes colours to match its habitat and deceive its prey in order to avoid being eaten. It is also about wishing to be confident but being shy and not wanting to be noticed at the same time. Painting and drawing the patterns for the installation and on my body was also a therapeutic process as it allowed me to focus my attention in one thing. Making this series was like performing a kind of ritual, which reminded me of African body painting. For instance, the Chokwe people of Angola use body painting for various reasons such as during courtship season, as an expression of being alive, or to show that two girls are best friends. I was also reminded of the male birds of paradise from the island of New Guinea that perform spectacular dances while showing off their glorious, brightly coloured feathers in front of their female counter part, as part of a courtship ritual. For me, the work is a type of therapy for self-healing, a way to explore my different personalities and as an expression of my identity.